Gilberto y Oscar Granja

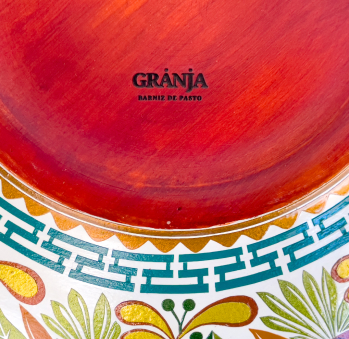

“Pasto Varnish is my old man.” These are the words of Óscar Granja, who inherited Gilberto Granja’s wisdom and became part of Nariño’s crafting institutions. He has spent more than six decades perfecting his technique. His works could easily be mistaken with computer-generated patterns: he is a master of his trade and, thus, unbelievably precise.

Óscar returned to Pasto in 2009 to work by his father’s side because he believed in the importance of preserving knowledge and in the need to adequately communicate the finesse of his craft. It was not an easy decision to make because he had been living far away from home for 22 years pursuing a career in architecture and graphic communications.

Regardless of how tough it was at the time, he knows that he made the right decision: it is the most gratifying thing he has ever done. He made a commitment to his home’s tradition and is doing everything he can to break the harmful cycles that have made artisan lives difficult for so long in Colombia. Óscar and his siblings used to help their father in his workshop when they were children: they learned the craft directly from his skillful hands. Nonetheless, he clearly remembers his parents urging him and his siblings to study. They did so because they did not want their children to endure what they had to: they did not want them to worry about not selling their crafts, or to break their backs working from dusk to dawn while middlemen and retailers keep all of the money that belonged to them.

Perhaps the event that left the deepest impression in Óscar’s mind happened when he overheard a conversation his father held with a customer at a Crafting Fair. When the latter asked Gilberto to whom would he pass his legacy onto, he said “I’m alone. My craft will die with me.” That moment shook him to his core. It brought forth all of the memories he had of his father. Since 1964, Gilberto had to work hard and build his life entirely from scratch.

Everything he tells about Pasto varnish comes from these memories: how it used to be made with white, mahogany, and red colors; how there is a fascinating gelatinous resin that comes from Putumayo and is called mopa-mopa; how he gradually learned to make lines, borders, letters, figures, landscapes, and everything that any master of this trade needs to know. In addition, the craft taught him to work with perspective and planes. He spent years learning all of this by watching, asking, and doing.

He steadily made a name for himself in Pasto. Finally, he started fashioning the Nariño bargueños —cabinets—, which have become a signature piece of the Granja hallmark. Óscar knows what his father is all about. He feels lucky to be able to give him back what he received in the shape of his talent. He is also proud to have added his marketing, communication, and negotiation skills to the family workshop. It is his way of making up for all the years that he was not by his father’s side. He strives to give the new generation of Granjas an appreciation for the past with an eye towards the future. The bridge between them continues to be the Galeras volcano: their greatest inspiration.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página