Miguel Ángel de La Cruz Imbacuan

Workshop: Taller escuela de alfarería réplicas precolombinas Sol de los pastos

Craft: Pottery and ceramics

Trail: Ipiales - Tumaco Route

Location: Ipiales, Nariño

Master Miguel Ángel de la Cruz was tied to Nariño by his love for his land and for craftsmanship, the same land that has inspired him since he was a child to create the ceramic pieces he currently makes. He grew up seeing how, when men plowed the fields to cultivate food, pre-Columbian ceramics from the Pasto and Quillacinga cultures would emerge from the earth. There was no need to search for them; they sprouted naturally. Despite being easily breakable, ceramics preserve well over the years, which is why Miguel Ángel’s father, Segundo Ángel de la Cruz, became a specialist in their restoration in order to return their integrity to broken pieces.

Through hands-on research, his father discovered the clays and techniques used by the original artisans. Over time, word of mouth and the quality of his work made him a renowned restorer, entrusted with pieces found throughout Colombia. At the time, the market for pre-Columbian pieces had not yet been regulated. Years later, when Miguel Ángel was already part of his father’s workshop and knew the secrets and details of the craft, the buying and selling of archaeological pieces was prohibited as these became national heritage, a necessary action to safeguard them.

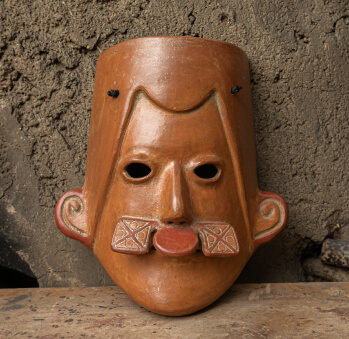

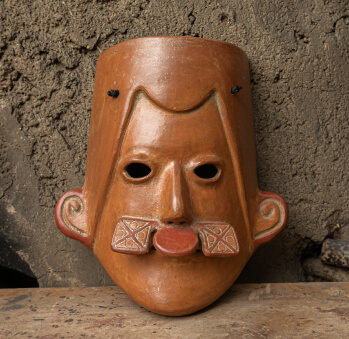

Instead of remaining idle in the face of change, Miguel Ángel de la Cruz decided to revamp his practice, drawing on the knowledge accumulated over the years. He began to replicate the pieces he used to document in notebooks long before owning a camera, which became his own encyclopedias of pre-Columbian art. He recreated maternity figures, mambeadores, and carriers, as well as typical instruments like flutes, ocarinas, and rondadores, which is what the Pasto people call their own clay pan flutes. Moreover, he adorned everything with the symbols that have always accompanied these figures: jaguars, lizards, snakes, eagles, frogs, and bats, under the eight points of the unmistakable Pasto sun.

The Master’s creations highlight his technique, rooted in his respect for the region’s ceramic tradition. After years of trial and error, he found that the ideal clay for recreating pre-Columbian pieces is a mixture of three kinds of clay—black, gray, and white—which together give the necessary plasticity, finesse, and fire resistance to his figures. Naturally, he finds them near Ipiales, as the ceramist’s deep and vital connection to his land cannot be interrupted, and he kneads them barefoot, reaffirming his place with each step. From this same territory emerge the colored clays that make up the traditional palette—red, cream, and black—that the Master uses to freehand draw the symbols that haunt his mind as clear and vivid images. He doesn’t need rules or stencils; his own pulse and a particular brush, made of his own hair, are enough to breathe life back into the sacred symbols with precision and symmetry. For the final step he uses Andean jade stone to polish his creations and lets them dry for a couple of days before burning them for just fifteen minutes, in the heat of precise flames, neither too high nor too low.

Several of the notebooks in which the Master and his father documented the pieces they restored have been lost over the years. However, he assures that, like a doctor, he keeps all the medications in his head. The shapes and symbols within him demand to be created, and just listening to him gives us an idea of the extent of his knowledge.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página