Ofelia Marín y Alida Márquez

Workshop: Ofelia: Interpretacion del bejuco al canasto

Alida: Artesanías Márquez

Craft: Basketmaking

Trail: Quindío Route

Location: Filandia, Quindío

Ofelia and Alida are sisters, traditional craftswomen, and proud Filandeñas. The childhood memory of going with their father to the woods in search of vines with which to weave the baskets that provided food for their family is engraved into their souls. They carried two or three dozen vines on their shoulders at a time and sold them between Filandia and Quimbaya. If you count their grandchildren, their basketry tradition already goes back five generations in time and has been around for more than a century in this small part of Quindío’s Eje Cafetero.

When they recall those arduous journeys through the woods, they feel more than nostalgia for the days gone by.

They also tell of how, for many years, this resource was aggressively extracted, which now forces people to go deeper into the forest to harvest it. They recount how they used to gently hang themselves from the cucharo or tripa e’perro vines to tear them from their trees. This is how they attained the 20-meter-long strips that would later be peeled into threads for weaving. The chusco, on the other hand, grows on the surface. This makes it so, to harvest it, one must carefully pluck it from the ground, removing all its roots, knots, and buds. In the past, the material was dried with charcoal stove smoke, which, incidentally, immunized it against bugs. Times have changed, however, and today it is usually dried on scaffolding under the sun. The old way of drying the vines gave a caramel tone to the fibers, while the sun whitens them.

Both sisters are quick to acknowledge that each one of these processes has its advantages and disadvantages. They understand that time gradually transforms the craft. One of the larger changes the trade had to suffer happened in the 1960s when the customary coffee-harvesting baskets began being replaced by plastic containers. This disrupted the region’s economy and forced its inhabitants to find new ways of preserving their weaving tradition. Ofelia describes this situation as a “necessary evil” that inevitably led Filandia to invent new basketry products. The town’s craftspeople started weaving lamps, vases, trays, trunks, and any wares that either designers or tourists wanted.

This particular craftswoman tried dyeing fibers with vegetables, plants, and seeds, which included beetroots, eucalyptus leaves, and achiote. She even designed costumes for beauty queens with traditional vines and catapulted the region’s typical yellow-eared parrot to the runways of Cartagena. Meanwhile, and aware of the increasing regulations around the use of vines, Alida has specialized in weaving plantain calceta: an equally beautiful —albeit much more readily available— raw material for weaving. She mixes vines and guascas experimenting with their differences and crafting innovative wares. Both sisters are proud of their family tradition.

To spread their knowledge, Ofelia and her son, Wilmar Jesús, established the Centro de Interpretación del Bejuco al Canasto (Interpretation Center: From Vine to Basket). It, aside from being a museum and showcasing the different steps involved in the craft, is a place where weaving is taught, and a wide range of products are offered. Alida, who lives in the San José neighborhood, passed her knowledge on to her daughter Jessica, who followed in her footsteps and now works to preserve their legacy with her skillful hands. Both of them know they share a common heritage. Nevertheless, they also enjoy introducing fresh ideas into their crafts influenced by the newer generations.

Craft

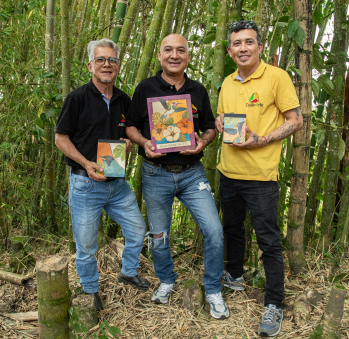

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página