Rubiela Grisales

Workshop: Juliana Grisales, tienda del bordado y diseño

Craft: Weaving and textile work

Trail: Valle del Cauca route

Location: Ansermanuevo, Valle del Cauca

SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT

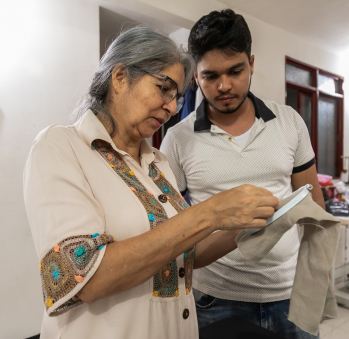

Rubiela Grisales came to calado embroidery through friendship—and through motherhood. She was seventeen, working at a coffee warehouse alongside her friend and neighbor, Leonor Herrera. When Leonor became pregnant, she set out to learn embroidery from her sister-in-law so she could make clothes for her baby, and she invited Rubiela to join her. They started five months before the baby was born, and soon Rubiela realized she could also sell what she made, even though she didn’t yet know this craft would become her life’s project. She quit the warehouse and stayed home, embroidering. That way she saved money on lunch, didn’t wear out her shoes or clothes, and could decide when to get up, work, and go to bed. What excited her most was the technique—realizing that you could create so many things by pulling threads from a piece of linen or cotton, and discovering that she was good at it, that she had the skill and creativity to combine stitches.

By the time she realized it, calados had become her path. She got married, had children, and just like her friend Leonor, she began making dresses for her daughter—which meant she had to learn patternmaking, too. Life slowly prepared her for what was to come, teaching her what she needed to eventually set up her own embroidery workshop. She began teaching other women, becoming part of a tradition that took root in Ansermanuevo: a town of artisans working as labor for the embroidery studios of Cartago. Ansermanuevo, a town whose economy once centered around coffee, millet, and corn, found new opportunity in calados—especially after the broca crisis of the late 1980s, the coffee pest that devastated crops and led even men to learn how to embroider and pull threads.

According to history, the craft came to Cartago with nuns from Spain—more specifically, from the Canary Islands—who arrived as teachers at the María Auxiliadora school. The technique evolved here: today it’s done using a hoop, but originally it was performed on table-like frames that forced embroiderers to hunch over. Rubiela has studied the history during the more than forty years she’s spent practicing the technique—and she says it with pride: more than forty years!

In that time, she has not only perfected her technique and created new combinations of stitches—beautifully named espíritu, punto de cruz (cross-stitch), malla (net), arroz (rice), telarañas (spiderwebs), and randas—but also learned to care for her most important tool: her body. To her friends, her apprentices, and even her husband and children, who work closely with her in the family workshop, she always gives one main piece of advice: always unthread under good lighting, to protect your eyes. And to preserve the skill of the hands, you have to protect them from sudden changes in temperature: don’t go out into the cold after cooking arepas over the fire, don’t wet your hands or shower right after working, no matter how hot the day is, and don’t go outside if there’s a breeze after your hands have warmed up from stitching. That’s the best way to protect your hands and eyes—and, in turn, the best way to care for the craft.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página