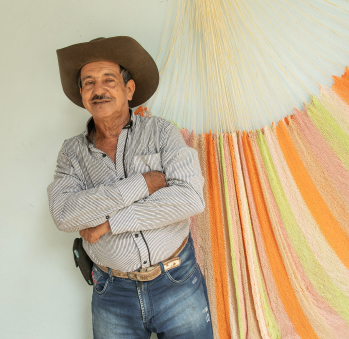

Wilmer Fabián Jaimes

Workshop: Arte y faena

Craft: Luthería y trabajo en hueso

Trail: Arauca Route

Location: Fortul, Arauca

In Wilmer Fabián’s narrative, his journey as a craftsman was akin to cracking a tough nut. It all commenced with a boy stricken with harp fever during his final high school years. He’d cart his harp to school, seizing any moment to practice, much to the frank annoyance of his classmates. Then, he enrolled in a Music Academy in Fortul, where he fixated solely on his instrument. However, merely six months after his enrollment, tragedy struck; his father passed away, leaving Wilmer an orphan.

As he resided with his father, Wilmer relocated to a friend’s house in Tame, Arauca. There, he commenced crafting his initial bone harp bridge pins. He discerned that these fittings, inlaid beneath the tuning pins to space the strings, were typically made from plastic but functioned better if fashioned from bone, enhancing the sound. Yet, polished bone emitted an unpleasant odor, leading Wilmer to once again irk those around him, this time with his craft.

Initially, Wilmer utilized bone from the front and hind cow legs for his experiments. However, upon considering producing on a larger scale, he realized his own food’s bones were insufficient. He needed to have bones for breakfast, lunch and dinner. So he approached cow leg jelly producers for the boiled and cleaned bones they discarded. Utilizing shins, a type of bone wide enough for crafting bridge pins, he catered to professional harp players who valued sound quality. Starting with samples, his clientele grew as word spread.

Vision has always guided this artisan. He understood early on that securing profits was crucial in artisanal work. Before the bridge pins, he experimented with chinchorro hammock weaving, a skill passed down from his uncle in Cúcuta. However, he found it unprofitable due to the extensive time and effort invested, making sales infrequent. Consequently, he prioritized choosing a craft that could sustain him financially.

Aside from crafting bridge pins, Wilmer makes maracas. He first experimented with coconut, which didn’t yield aesthetically pleasing results. Years later, he revisited maraca-making, this time using totumo, a softer material with excellent acoustics. Filling them with capacho seeds sourced from the Uwa people, indigenous to the Norte de Santander mountains, he discovered their suitability for open spaces due to their robust sound. Conversely, espumaesapo seeds proved ideal for closed environments like recording studios, ensuring the maracas didn’t overpower other instruments in Llano music bands: the harp, cuato and the singer’s voice.

In his quest to distinguish his maracas, Wilmer ventured into pyrography, adorning them with typical Llano scenes like capybaras and horses. However, despite his efforts, he could only produce twenty pairs per month independently, which fell short. A sleepless night led to a revelation; he prayed for guidance, and a solution presented itself—mechanizing his production, saving his maracas and bridge pins business.

Currently, apart from being an artisan, Wilmer dedicates himself to education. He instructs kids aged 11 and above in five institutions, including his alma mater, the same school where he once irked classmates with his harp. Teaching harp, cuatro, and maracas for 19 years, he mirrors his father’s approach in connecting with each student. His father, a music enthusiast who played various instruments including the acoustic and electric guitar, and the acordeon, instilled in Wilmer a passion for music. Although singing isn’t his forte, people dance whenever he plays. So, when you visit him, ask for a Llanero song while sipping on his homemade masato, a rice fermented beverage.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página