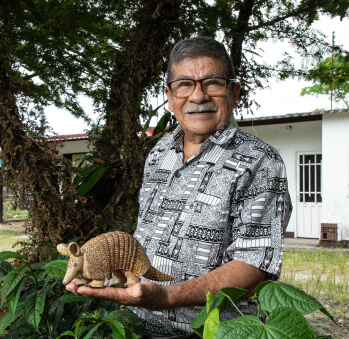

Avelino Moreno

Workshop: Artesanías típicas Avelino Moreno

Craft: Luthería

Trail: Casanare Route

Location: Tauramena, Casanare

Talent is evident in those who possess it, and Avelino certainly has it. When music runs in your veins, nothing can impede its course, not even the silence of your home or the lack of available instruments. In Avelino’s case, musical awareness awakened at an early age as he heard his elders play the guitar and sing songs about fieldwork. He was drawn to their beautiful laments. Later, when he started to work as a day laborer, he preferred to be close to a river for a bath, to have a black and white T.V. for checking the news, and, most importantly, have instruments nearby to light the evening with llanero songs.

His preference for the music of his homeland grew as he tuned into local radio stations. Radio Táchira and La voz del Cinaruco introduced him to the magnificent richness of joropo. He later learned to handle cowhorn, bone, and wood, crafting necklaces and accessories he could trade for batteries for his radio. That radio adorned his nights and dawns with his favorite lullabies. For example, one of Juan Farfán’s first songs, forever engraved in his heart, where he sang, “”Orioles and jays sang their laments, flew from branch to branch and then stood silent, contemplating and appreciating the sorrow of guava trees.””

When he tells his own story, filled with the details and memories that make him an exceptional storyteller, it’s clear that it all began when he lay on a chinchorro as a child. Letting his head hang from the hammock, its slow movement resulted in a string sound tuned in a chord that would never leave him. From then on, he made it his mission to make music. With no available instruments around, he used his brother’s memory. His brother, the other musician in the family, had the opportunity to watch the bandola courses taught by songwriter Dúmar Aljure Rivas while accompanying their mother to her literacy classes. So Avelino asked him to teach him what he had seen—the hand movements over the strings, which he imitated on a wooden piece, imagining it was an instrument. Then, his enthusiasm led him to carve and tighten the chinchorros’ nylon to resemble the strings and devise the tuner pegs to complete his bandola. They tried hard to find the desired sound until they achieved it.

Many years have passed since he bought his first cuatro guitar with his hard-earned money when he was sixteen. Many years have also passed since he first saw an instrument with a sounding board made from a totumo—a cirrampla. He came to know cirramplas and furrucos, traditional instruments that he would later craft himself. He recalls the first time he held an instrument in his hands, disassembled it, and reassembled it until he achieved a perfect D major. However, it wasn’t until he reached his thirties and got married that he fully embraced music. He first learned to repair instruments and later, armed with the knowledge he had acquired in his teenage years, he began crafting them. He would become a renowned luthier and manufacturer.

Having mastered the craft of making traditional llanero stringed instruments—cuatros, bandolas, and mandolinas—he ventured into creating ancestral cirramplas and furrucos, bass instruments. Now, he acknowledges having become an authority in luthier work, and thanks to his efforts and promotion, these instruments are no longer ending up as mere display pieces in a museum but are being played.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página