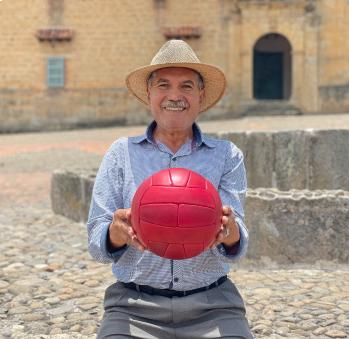

Édgar Ladino Saenz

Workshop: Balones Ladinos

Craft: Marroquinería

Trail: Paipa-Iza and Paipa - Guacamayas Route

Location: Monguí, Boyacá

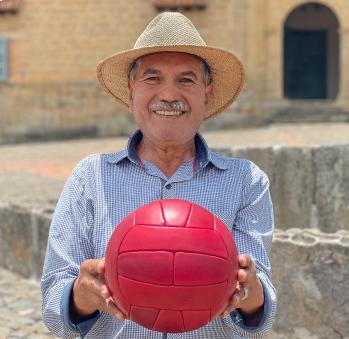

Even though he is the heir to the king of balls, he is all about cycling. Nonetheless, the intensity, grace, and knowledge with which he speaks of his family’s tradition leads you to believe that this man is driven by passion. He says that the trade reached Monguí thanks to the War with Peru in 1932, and that it did in the hands of his uncle, Froilán Ladino, founder of the Ladino Balls dynasty. Due to a transfer to Manaus on the Brazilian border, Froilán witnessed how a jail’s inmates made footballs and he tied the strings together to notice that the large-scale production was testimony of a soccer-loving country. He carefully observed how they got made and returned to his town by Boyacá’s mountainside with the obsession of replicating his idea. His drive was able to modify the local economy —which had always been dependent on agriculture and, starting in the sixties, to mining due to the newly established steel company Acerías Paz del Rio— for a while.

Froilán had the soul of an inventor, so he locked himself up in the workshop and tasked himself with designing the machines with which the famous footballs that are now part of Monguí’s heritage were going to be made. He made a die-cutting machine that he proudly marked with his initials, FLA, and aluminum molds with which to shape the ball that makes so many millions of people around the world happy. With the machines ready, he turned to what the townsfolk had always known how to do: sewing. There, women’s hands started joining together the die-cut pieces with threads and needles. They made what would be the first of Monguí’s footballs in 1938 baptized with the brand Libertad. It cost only 20 cents, as can be seen in the records. Because of this, in honor of those hundreds of women who were embodied in Doña Matilde Holguñin, there is a sculpture of the weaver in the town’s main square. 21 different sewn football models were designed in Monguí, always following trends and the styles of the World Cup balls.

Édgar delights in recounting detail by detail these origins. He says that, being a “’65 Model”, he witnessed the golden age of the Monguí football in the seventies. It was a manual industry that gave jobs to 350 families for years and that, with its more than 1,000 craftspeople, created a regional symbol. In fact, the market was so big that the town’s families —mainly the Ladinos and the Acevedos— split the country among themselves to distribute the 14,000 footballs produced monthly in Monguí. His grandfather, Manuel, went to the south —Cali, Ipiales, and the border with Ecuador— with the Supersoria football; his father, Paulino, went to Medellín, the Caribbean Coast, Santander, and Bogotá. Moreover, if the children helped in the workshops during vacations and assisted their mother bringing the raw materials to the ball stitchers, the prize for any of the seven Ladino siblings was to go with their father in his trips around Colombia. This delivery of leather on Saturdays, market and payday, was a ritual: every one of the 12, 18, or 32 die-cut pieces got marked with a number and placed in pairs tied with a string so the artisan can sew them upside down.

That being said, times have changed. Since the birth of the new millennium, footballs have started getting made with vulcanization, an industrial process. This has made sewn balls a unique and lasting ware. A cult of manual craftsmanship and a luxury undoubtedly caused by the enormous amount of work involved. Édgar does not want this tradition to become extinct. That is why he continues tirelessly practicing his craft. He even made a museum to preserve the memory of a little town lost in Boyacá that produced 95% of the footballs that got purchased in Colombia and that, of continuing to grow, today could be Latin America’s Pakistan (this is an allusion to the town of Sialkot, which produces 40% of the global market of footballs and creates more than 600,000 jobs. But that is another story.) He has no regrets, he just wants the new generations to have the fortune of knowing Monguí’s footballs and, thus, be able to take this precious handmade round ball with themselves.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página