Francisco Silva

As a child, Francisco Silva believed his mother had a superpower: she never needed to sleep. When he and his siblings went to bed, she was still working beside them in their shared room—and when they woke up, there she was, still working. The truth was, Doña Elsa Gómez would go to bed at ten and rise at four to make her tightly wound, colorful fique vases—those that define Guacamayas, Boyacá. The family lived off agriculture, surviving between harvests of potatoes, maize, wheat, and peas. In the lean months, she wove baskets to earn enough for panela, rice, and meat—the few things they couldn’t grow themselves.

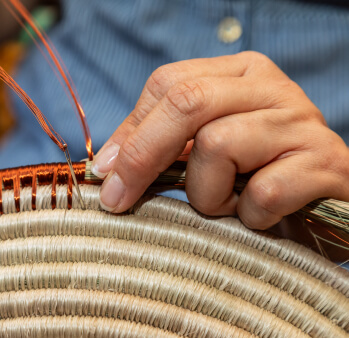

Francisco likely inherited her willpower. He never tires of working, his eyesight is sharp, and his hands never ache. He remembers how, as a toddler, he’d crawl over to her while she was weaving, only to be gently poked with her needle—a signal to turn around and let her be. Or perhaps he got it from his grandfather, Don Publio Gómez, one of the first artisans from Guacamayas to have his pieces displayed at the Museum of Arts and Popular Traditions in Bogotá. It was through those pieces that the town’s tradition slowly gained recognition. Francisco remembers his grandfather’s house full of baskets and carrieles, small bags for keeping papers—some woven with rolls thinner than what Francisco himself uses today. Back then, everything was made in natural color, and the inner core of the coils wasn’t straw, but fique itself—a sign of true refinement.

Francisco’s stubbornness is a kind of rebellion. At a time when young people were expected to leave town for better futures—preferably in Bogotá—he stayed. He didn’t want to leave his place. He worked in the fields, harvesting potatoes, wheat, and corn, until one day, the itch returned: he realized he could earn as much as a fieldhand by staying home and weaving paneras, just like he used to do in school—one basket a week to buy his snacks. He didn’t have to work under the sun or in the rain. Of course, people thought he was lazy. His coworkers mocked him. But he persisted—and it paid off. It’s been over 25 years since he began living from his craft.

The struggle didn’t end there. Materials became a problem. The fique they once bought in San Mateo, just an hour from Guacamayas, disappeared when locals abandoned farming for coal mining. So Francisco took the initiative to source it from Curití, Santander. That, in itself, is a story. The first time he bought it, he had never seen it before. The minimum order was 50 kilos, but he took the risk. It wasn’t until three years later that his supplier finally saw one of Francisco’s finished pieces and understood what the fiber was being bought for.

Then there was the straw. It began to vanish from the hills, and no one knew how to cultivate it—it grows where it pleases. At first, they would pull it out by the root, but that killed the plant. Then they tried cutting it, until they realized it would go to seed and die anyway. Finally, they learned to thin it out gently. Still, Francisco wanted more control. He brought some plants from Medellín and planted them outside his workshop. Though they can cut your hands if mishandled, they’ve learned to blend this variety with the local one. The result: lighter pieces.

His mother—still tireless—continues to work. If invited on a trip, she’ll say: why waste time walking when I could be weaving a bowl or a fruit basket? Truth is, neither of them can sit still. It’s what they love. Now, a grandson has arrived—bringing Francisco face to face with his own legacy. The boy isn’t even ten and already says he’ll stay in Guacamayas and dedicate himself to crafts. And even though Francisco did just that, and did well—so well that he won the Contemporary Master Artisan Medal in 2020—part of him fears for his grandson.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página