Nelcy Leonor Rincón

Workshop: Cestería de Leo

Craft: Basketry

Trail: Paipa-Iza and Paipa - Guacamayas Route

Location: Cerinza, Boyacá

SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT

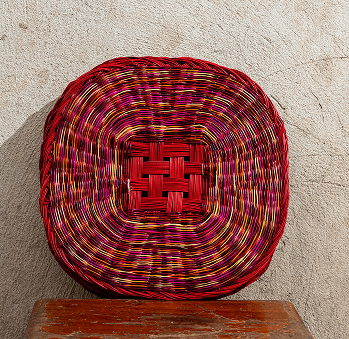

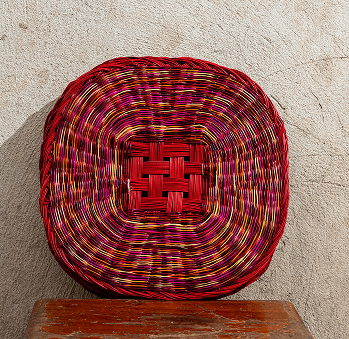

According to tradition, it all began with strainers—the mother of all baskets. That’s what Nelcy Leonor Rincón tells us. These coladores, once found in every home in Cerinza, were used to strain cuchuco broth, coffee, and milk for making cheese. Their fibers marked the cheese’s surface and gave the coffee its flavor. No one knows who first wove them, but their legacy is clear: from them came all the other forms—egg baskets, market baskets, placemats, cazuelas, vases, bread trays. All of these concentric pieces share a first step in their making: the crossing of pairs of esparto strands.

Perhaps it makes sense that the strainer was first. Esparto grows in highlands where water trickles between the plants, gathering into streams. And to shape the fiber, you have to moisten it. Esparto is temperamental—it doesn’t grow where you tell it to, but where it wants to. It clings to the earth, so harvesters must know just how to pull it. And it’s hard, physical work. Tools aren’t allowed: if you cut it, it dies. You must uproot it with your hands so it can grow back—like a weed. But if treated well, it gives generously.

People sometimes ask Nelcy if her baskets are made of plastic. The shine is so perfect, the fiber looks synthetic. But no—it’s the result of care. First, the fiber must be properly washed, then cooked for the right number of hours, then dried outdoors for fifteen days—no rain, no strong sun. The gleam appears as they weave, brought out by their touch.

In the hands of Nelcy and her team—five women, all heads of household, and one man who learned the craft after a life-altering experience—esparto transforms into something beautiful. Each one has a specialty. Nelcy herself is a master of the left-hand finish—a way of edging placemats. Doña Nubia is flawless at coiled edging. Mr. Valderrama creates double-walled fruit bowls. Doña Mercedes is known for her thick stitches, called sarga. Doña Floralba and her daughter Adriana excel at traditional designs. They all learned long ago, back when a dozen cazuelas sold for 2,500 pesos and placemats for 800. Nelcy remembers how, before learning to work with esparto by watching a local association of women, her mother had taught her to make the woven tops of espadrilles on a small loom with hemp thread. A dozen of those sold for 200 pesos.

That’s how life flows in Cerinza—women weaving baskets as they tend cattle, prepare food, and cook lunch. Nelcy has been in the trade for over thirty years, balancing basketry with caring for cows. For her, weaving in esparto is the best way to relieve stress. It soothes her. It flows from the heart. Stitch by stitch, she has sustained her family and passed her knowledge to two of her children: Jenny and Samuel David, a boy whose love for the craft is written all over him. With a smile bigger than he is, he offers everything his mother makes—and finds a buyer for every piece.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página