Ramiro y Diana Carolina Moreno Gaitán

Workshop: Grupo Kajuyali

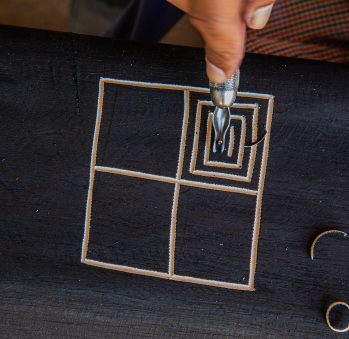

Craft: Trabajos en madera y tejeduría

Trail: Meta Route

Location: Puerto Gaitán, Meta

Ramiro, a member of the Sikuani indigenous group, learned everything he knows from his father, from whom he also inherited his name. His indigenous community, comprising 22,000 inhabitants, is spread across four settlements.

Sikuani thinking revolves around the principles of solidarity among its people and reconciliation with its rivals. For Ramiro, their most potent tool is unity and mutual support. However, he is well aware of the impact of capitalism on their age-old customs. The rapid expansion of agricultural projects threatens to encroach upon their territory, eventually forcing them to alter their way of life. Over a ten-year period, he has witnessed a profound transformation in their homeland. Yet, he remains resolute that they will continue to reside in their territory, as they were born there and have no other place to call home.

This is why he places great emphasis on cultural resistance and holds his elders, their traditions, recipes, and beliefs in deep reverence. He is dedicated to preserving these cultural elements, no matter the challenges. Ramiro firmly believes that education is the path forward and will enable them to “”defend what little remains”” by helping the new generations of Sikuani people find their place in a globalized world.

Craftsmanship plays a vital role in the revitalization of their ancestral traditions. Before being considered as crafts, these items were a part of everyday life in their households. It all started when a woman who witnessed Ramiro’s woodworking skills recognized the beauty and significance of his pieces. She told the patriarch of the Moreno family that the story of his people, as told through his thought benches made of wood, deserved to be shared. Having worked in the labor-intensive rubber fields of the Vaupés rainforests for over thirty years, he would seek refuge and a way to reconnect with his roots by crafting these benches. This marked the beginning of their work as woodcarvers, and they also initiated a reforestation campaign for the machaco tree to ensure the preservation of their customs.

Ramiro’s son, also named Ramiro, has learned the craft and deeply understands its symbolic significance. He recognizes the profound symbolism surrounding these benches and, as a result, he crafts them with great care and respect for the tradition. After carving them, he adorns them with arrayán or putty made from the guamo loro tree, creating a striking contrast between the liquid from the tree’s vibrant red bark and the black color.

A thought bench is unlike any other chair. One type serves ceremonial or ritual purposes, while the other has mythological significance. The former is used, for example, by a girl during her menarche. While sitting on it, she receives essential instructions for transitioning into adulthood. The bench serves as a place where she is blessed with prayers for protection against the fish, a malevolent being that manifests through these animals, potentially leading her to his waters or inflicting illness. The latter, a mythological bench, features representations of rainforest animals such as anteaters, alligators, and armadillos, each with its own unique symbolism. For instance, the Soki tiger, one of the guardians of the Sikuani people, is depicted with a red tail, representing its territorial boundaries marked by fire. There’s also the two-headed turtle, a morrocoy turtle, symbolizing the choice each person makes between a good or bad life path.

Taking a seat on a thought bench necessitates an openness to introspection and a willingness to listen to the elders. They don’t provide lectures but rather reveal the potential consequences of one’s future choices, granting the freedom to choose one’s path. As Ramiro aptly puts it, once you’ve sat on a thought bench, you can’t claim ignorance of the implications of your decisions. These wooden animals that take the form of thought benches foster heightened awareness of our actions by representing the moral dimension of the choices we make.

Standing alongside Ramiro is his wife, Diana. She is the daughter of a white man and a Sikuani woman who left her community for 24 years to work in Bogotá and Fusagasugá. Despite growing up in both worlds, Diana ultimately returned to her mother’s community, where she learned to weave with moriche palm fibers and create traditional ethnic beaded jewelry, alongside her husband and mother-in-law. She handcrafts woven necklaces and bracelets used during the prayers of the fish. She is a devout believer in the fish myth, having been possessed by the fish during her puberty due to a lack of prayers. At that time, she experienced remarkably beautiful dreams and substantial weight loss, both signs of something amiss. Traditional healers had to intervene with prayers to liberate her. She repeated this ritual with each of her four pregnancies.

Both Ramiro and Diana live in accordance with their beliefs, endeavoring to preserve their culture through each of their crafts, bridging their world with ours.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página