Sombrero Aguadeño

Workshop: Taller de Ripiado El Jardin, El Taller del Sombrero y Corporación Virgen de la Loma

Craft: Weaving

Trail: Caldas Route

Location: Aguadas, Eje Cafetero

MARTA BEDOYA

THE RIPPERS

Daughter of a ripper, skillful ripper herself and married to a ripper, Martha Bedoya has given her life to the art of growing iraca palm and preparing it so other hands may use its fiber weaving the traditional Aguadeño hats. She speaks fondly of this plant, which has been with her since she was a girl. She gives generous thanks to it because everything she has, she owes to its flexible skin, which, in the shape of a palm, exposes itself to our eyes with its splendorous geometry and verdure, and, in the shape of a handcrafted ware, crowns whoever wears it.

There was a time in the first half of last century when you could find a lot of iraca palm in this part of Caldas. There is talk of more than 100 acres planted with this palm. It was the livelihood of many towns, among which was Aguadas. But, as one thing goes hand in hand with another, economies shifted priorities, and many landowners who had planted iraca changed their use of the land with the introduction of livestock. It was easier and more productive to own cattle than to wait slowly for palms to be ripe for harvesting. This choice, as well as the steadfast wager for an agricultural economy based in coffee, made works with the palm (among which was weaving) become a minor trade, even though, paradoxically, it is a symbol of regional identity. Despite of all the setbacks, the Aguadeño hat has managed to earn the Denomination of Origin acknowledgement and has taken its place in history, even if few have become rich with its craft.

This is the context in which Martha has lived. In spite of witnessing the changing times and knowing herself to be one of the very last rippers left in the region, she has seen every one of the iraca palms she has planted in the five acres where she lives grow. She has lovingly taken care of them in their first years of life —as defining as in human children—. She has seen their stems and leaves grow and has pampered them, so the palms never stop producing for the 30 years that follow the moment they are ready. She speaks of the hearts that this lush palm produces as if she spoke of her very own children. And they are, for the success of the process depends on the attention she pays when planting and harvesting on time —neither when they are “niñitas,” as they are called when they are unripe, nor “jechas,” as they are called when they are overripe and will burst—. A stage that finishes with the ripping, which will determine the quality of the hat that will be woven with the fine vegetable fibers.

And it is the rippers who “comb” the fiber with a series of nails and extract the threads of the palm according to the thickness the weaver asks for. These include the extrafine, the fine, and the common thicknesses, being the narrowest threads the ones that produce the finest hats and the ones that demand the largest amounts of both raw materials and work. Making these threads, which get twisted in quarters, is long and tedious, since, after planting and harvesting —the latter of which must preferably be carried out at the change of the moon to bring out its best qualities, as when you cut your hair—, comes cooking the fiber, drying it, leaving it under the sun, soaking it, and mixing sulfur with it, which is what will fix the palm’s cream color, characteristic of the Aguadeño hat. Martha asks us to notice the particular qualities of the fiber’s colors with the intention of understanding time: when it is harvested, it is green; when it is cooked, it is yellow; when it is dried under the sun, it becomes gray; and then, with the sulfur on the stove, it turns evenly white, a distinctive sign of when it’s ready to be woven.

She also says that how much iraca has been spent has created a way of keeping accounts: a palm’s weight are 320 hearts. And Martha, alongside her husband, are able to rip in a two-day sitting 10 weights. When there there has been high demand, they have even reached 16 weights, meaning 3,000 hearts. This is just the beginning of the proces, which will then take another week to ready the fiber. The rippers, the people who prepare iraca fibers for art, go into town early on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays to sell their product. These are the moments when we understand the tight bond and the relationship of trust that is established between a ripper and a weaver, both figures honoring nature with their hands and, through their beautiful work, making town’s symnbol.

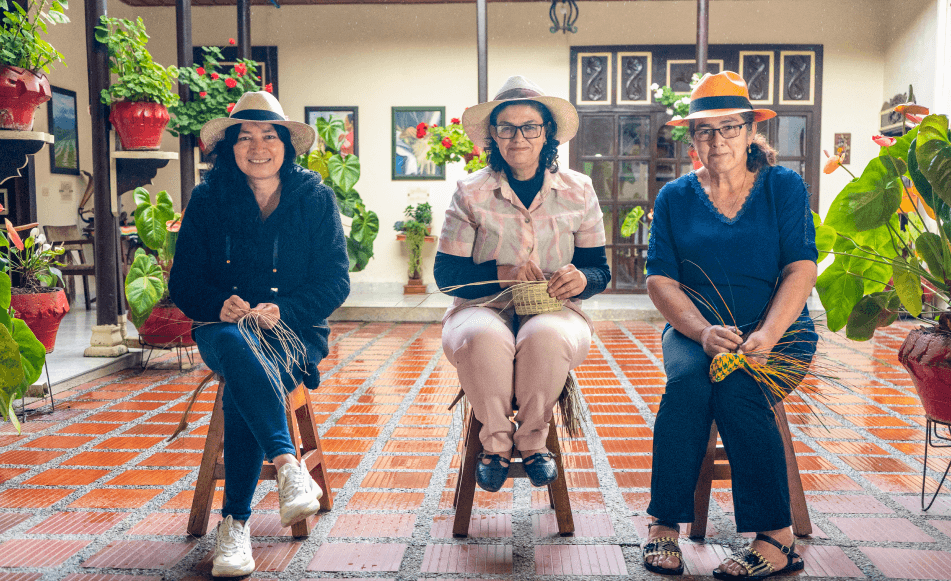

BLANCA IRMA MARTÍNEZ, DORA ELSY CARDONA Y MARTHA LOTERO

THE WEAVERS

These women were born in Aguadas and have the weaving tradition flowing through their veins. They learned it from their mothers, and their mothers did so from their mothers as well: it is natural for the women of the house to know how to weave. Martha Lotero, already having more than thirty years of experience weaving hats and other wares with iraca palm and earning her livelihood from it, is thankful for having been forced to learn because she knows that, if her mother hadn’t done so, her house’s tradition would have ended. Dora Elsy Cardona, on the other hand, says that, contrary to many weavers who learned by pinches and pinches, she did so without fears and with pleasure. And she taught in that way to her lineage as well. Blanca Irma Martínez’s mother and grandmother taught everything to her when she was but a wide-eyed, curious girl. They started with the bottle holders, with seven straws with which she made a string. From there, she rapidly went to learning how to craft a hat and the hurdle that is its start and the four rises or spirals with which a fine hat’s crown is made. Blanca always speaks of doing her job in a “polished and careful” way, as she was taught, tightening the fibers together very strongly. She has the memory of watching her mother come home with the straw that she herself carried.

She gets fascinated when saying that she has been weaving for 45 years. That is to say, her entire life. The life of every one of them.

Virtually all repeat the same story: they helped their mothers raise their siblings and have the memory of joining the rest of the family in crafting the hats with which they earned their livelihoods. They remember harsh and demanding childhoods, but none of them regrets having lent their hands to learning the art to which they have devoted their lives. They are friends of the fibers and know how to see and use the raw materials they get. They have learned along the way how to braid it more or less tightly, as requested, and how to thus make an extrafine, a fine, and a common hat. Each one of them will serve a different purpose and, of course, will have a price in accordance with the hours spent working on it. They know themselves to be further continuing a living tradition.

The weavers from Aguadas mix the trade of weaving with the household chores: with cooking and raising their children. They do so, not only because that is the way it has been done for years, but because it is virtually impossible to spend an entire day working due to the how physically demanding the technique is: the body stays hunched, the hands, tight, and the eyes, focused; aside from the effects the sulfur that is used to dye the fibers with has on the fingers. Weaving is, then, something they have learned to do meticulously and with a muscle memory that only they have. This is why they can afford the luxury of talking or watching television while they work, as Dora Elsy says laughing. The hat will be ready in a few days: sometimes two, others seven, and some even a month, depending on the quality of the order.

The weavers know the work it takes to make one of the tighter hats —the extrafines— and are aware of the fact that they are precious pieces that only a few are willing to invest on: a jewel of nature mediated by a woman’s hands. And that they are not widely available.

Hence, they dedicate their technical mastery and their dominion over their trade to hats that are less dense and that, in any case, will be bent: another characteristic of the Aguadeño hat due to how marvelous a fiber iraca is. No task is too big for these women. They learned several techniques by trial and error and thanks to customers who asked them to do this or that design, and to whom they could not refuse. Martha remembers that she earned a pressure-cooker and 100,000 pesos because of weaving some baskets with her mother more than 30 years ago. That fact made them enjoy diversifying the use of iraca into an endless number of artisanal products. Dora Elsy makes hats, but she also crafts coasters, fans, and bags. Many of them also work passing their knowledge on. Martha does it, and she loves doing it. Dora Elsy does too. And Blanca Irma left her knowledge to her nephews. Because it is what they have always done with their hands and a fiber that is called “iraca.”

DIEGO RAMÍREZ Y DIEGO ARIAS

THE FINISHERS

These men represent the last stage of making the Aguadeño hat, and they are called “finishers.” Normally, they are in charge of selling them afterwards as well. They receive the hat from the weavers while it is still “hairy” or “en rama,” meaning that the straws with which it was woven are still long on the hat’s flap and still round or flat on its crown. This is why their task is to “peluquiarlo” or weave the edge of the flap, put the characteristic black ribbon on it, and give it its size and fit. The finishes. They put the woven iraca in a manual aluminum press where it has to undertake 150 degrees of temperature for its crown to get the folds that made it famous and that are also a guide to be able to bend the hat without breaking it. Ramírez claims that way back in the 1950’s the Aguadeño hat was shaped with an iron and that, even though many put the hat in automatic presses, he still preserves the manual work because he vouches for responsible use of energy and protecting the environment, insisting upon the biodegradable aspect of the hat.

Both links of the chain, weaver and finisher, need one another, and it is interesting to see what is the way in which they share the loads of the trade in Aguadeño culture. The finishers have appropriated the myth of the hat’s creation and have turned into the transmitters of their story. They portray the “paisa” aura and proudly bear the name that one of them got in 1979: “El Putas de Aguadas,” which is no more and no less than the living embodiment of the paisa witty character who “entangles,” who solves everything with words, and who is ready for anything. As Diego Ramírez well explains, whoever arrives in town should not bring firewood to the forest, that is to say, should come willing to be served, because, as it is said there, “do not bring a machete to Aguadas, we give it here… the people of Aguadas push cars, donate blood, lend money, and swear in vain. This is Aguadeño race: we are strong people, we are people who move forward, and not just for our bellies.” He says this gracefully and with laughter, owning the nickname that was left to all of them by Juan Ramón Grisales’s book that baptized them as “Putas.”

But everybody has their personality, of course. Because Diego Arias, unlike his namesake, has had an almost missionary role in the Aguadeño tradition. Along with his priest brother, they established the Virgen de la Loma Artisanal Cooperative, creating the icon of the Virgin weaver. With her, they accompany weavers from the faith and seek to find fairer channels for them to market their hats. He has also told his stories in long video interviews that circulate in a digital television channel. Their commitment to them is absolute. These two men know that, as Diego Ramírez says: “the weavers are the artists, they are the ones who deserve all the acknowledgement in crafting Aguadeño hats.” For that reason, they are an example of how to relate ethically to the craftswomen we suggest you meet. They are convinced that this is the only way of guaranteeing that tradition is preserved and that the business treats each one of its links fairly and transparently.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página