Teodora del Carmen Suárez Gaspar

Workshop: Arte Diseño Zenú

Craft: Weaving

Trail: Bolívar Route

Location: Arjona, Bolívar

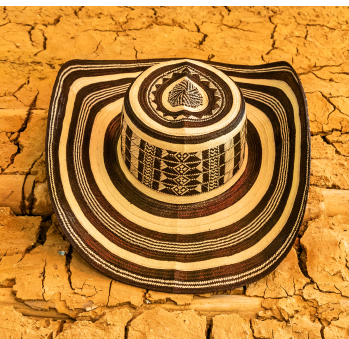

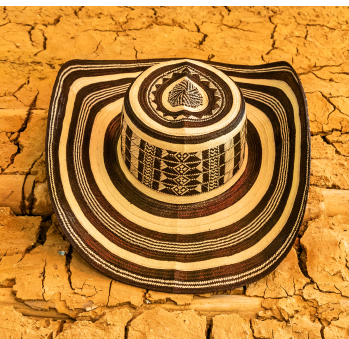

What do the parts of a vueltiao hat mean? As Teodora del Carmen explains, they symbolize the stages of life itself. The beginning, the center from which the rest of the hat grows, is like the birth of a child. The crown expands as the child grows, representing their childhood, which culminates with the transition into adolescence, followed by the brim of the hat, symbolizing the adulthood of each person. Finally, the last turn of the hat, at the edge from which there’s no return, represents old age and the end of life. Teodora learned all this from her mother, Candelaria Mendoza Suárez, in the Zenú Indigenous Reserve of Córdoba, in Tuchín, where she was born and raised. It was there that her life began to take its first hat turns, and she learned to make her first braids at a time when children’s education was centered around the transmission of customs, the care of nature that lies at the heart of their culture—one that knows how to work the land, plant, preserve the forests, and live off everything that grows from the Earth.It was a very different environment from her current life in Arjona, Bolívar, where teaching her grandchildren has to fit into the little free time they have between school and homework. Whenever she can, she takes them to the woods to collect bija and singamochila plants, and clay for dyeing the caña flecha, their raw material for weving hats. She slowly teaches them how to make the braids, so the culture won’t be lost.

Then they had to leave the Reserve. Her mother took them to Arjona, where, when life became difficult for Teodora, reconnecting with her Zenú roots was the only thing that saved her. She had lost her husband and was left alone with five children. She tried everything to get ahead—taking courses in food handling, vegetable farming, hairdressing, manicure, and even shampoo production—but none of it worked because none of it interested her. Then she understood the teachings of her mother, who had always insisted that Teodora sit down and weave. She realized what her mother meant when she said, “”Mija, if I taught you something, enjoy it and make the most of it.”” And that’s exactly what she did. Instead of selling mangoes and pineapples, she decided to stay home and weave, finding a way to be there for her children without leaving them alone until nightfall, unprotected and exposed to bad influences. She learned to reconcile raising her children with working, and to live off the talent she carried in her hands.

She then gathered the wise women around her: the one who knew how to make the best dyes, the one who braided the fastest, and the one who wove the quickest. At first, she would take the high-quality braids she made to Tuchín to have them sewn together, but eventually, she learned to sew herself and bought a sewing machine so she wouldn’t risk having her carefully crafted braids swapped out. None of this would have been possible without the help she received from the Sena , Artesanías de Colombia, and her Church. She knows that her strength comes from her immense Christian faith, which she has been able to blend with the Indigenous principles that guide her as the world changes and life presents new challenges.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página