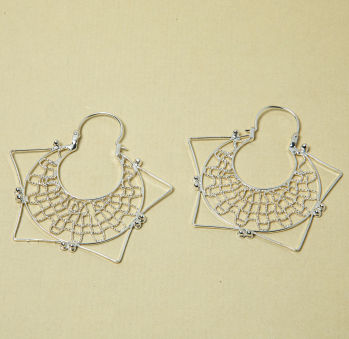

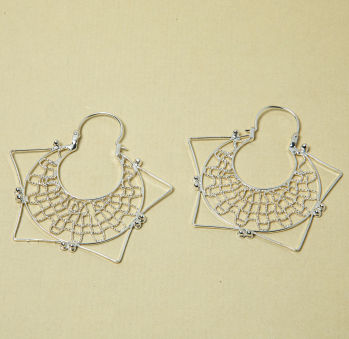

Albeny Navarrete y Arte y Joyas

Workshop: Arte y Joyas

Craft: Jewelry

Trail: Risaralda Route

Location: Quinchía, Risaralda

SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT

Calle 6 #7-15

3117619490

artejoyas58@gmail.com

@arteyjoyasquinchia

@rteyjoyasquinchia

Working in a jewelry workshop in downtown Quinchía—crafting filigree, chainwork, and casting—wouldn’t mean the same without knowing the long path people take to find the precious material: gold. That elusive, coveted metal that has fueled so many dreams with its shine and has shaped the history of the towns where it hides beneath the soil. Without going as far back as the legend of El Dorado, Quinchía itself is proof that the town’s economy and livelihoods have always revolved around gold. Its history has been molded by artisanal mines, families camping by the river in search of it, and now by private mining operations, while other families dig ever deeper along the riverbanks to find it.

Albeny Navarrete grew up in this gold town, searching for it in the streams and along the Cauca and Opirama rivers during her family’s mining journeys. From the age of seven she joined her mother and uncles, setting out on Mondays to camp until Fridays, living off the catfish and bocachico her uncle caught each evening with the hooks he had set that morning. She worked with them until she was thirteen, back when gold was still found in riverbanks, dug from pits barely a meter and a half deep, washing the gray sand in wooden pans. Eventually, Albeny left the mining work when she learned to sew and stayed home sewing. But gold found her again: first through her husband, who began working in a mine after they married, and later, in the late 1990s, when a governor—keen to see Quinchía’s gold leave the town transformed—brought in a filigree master from Chocó to train locals, a path later expanded by workshops through Artesanías de Colombia.

Those trainings included Albeny Navarrete, Amanda Ladino—who almost didn’t get in because the class was full, though thankfully she insisted, otherwise she wouldn’t be part of this story—and Efraín Molina, who would later join with Keira Hernández to form Arte y Joyas. Like Albeny, Efraín had also known gold closely before the workshop. He calls the workshop “dry and comfortable” compared to the mines where he once worked, where water constantly seeped in, and the tunnels were so narrow that sometimes there wasn’t enough air. In the workshop, there are no such risks—no dynamite to blast open mountains, no relentless heat, sweat, and water, no toll on the body after years of crawling through cramped passages that damage joints, backs, hands, and feet. That was the reality of mining in his twelve years underground, especially in those days before the stricter regulations that, while making mines safer with tunnels two meters high and eighty centimeters wide, also brought privatization and foreign ownership.

These jewelers have seen the landscape change. They have moved from gathering gold directly from the earth to delivering it as jewels and adornments. They’ve also witnessed another shift: back when they were just starting, it was a tradition for families to commission a gold ring for each graduating child, when a gram of gold cost only 13,000 pesos, and everyone in town wore golden chains and earrings. Now, silver dominates the workshop. As gold became scarcer and its price climbed past 400,000 pesos per gram, people began to see it less as adornment and more as investment. Those who still search for it along the riverbanks now must dig deeper, carving steep L-shaped pits that reach beneath the water itself to find traces of gold.

And yet, the love for the material remains—that deep knowledge of how to treat a metal, how to transform it into beautiful pieces inspired by their Hills Tow, Quinchía. Especially by the Gobia Hill and by the ceremonial makeup once worn by the Irras and Tapascos, the ancestral peoples of these lands, in the time when the dream of El Dorado still shimmered in the imagination.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página