Diego Urán

Workshop: Taller De Joyería Juan Urán Arias

Craft: Joyería/bisutería

Trail: Cordoba Route

Location: Ciénaga de Oro, Córdoba

SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT

Calle 4 # 19-31 Barrio Santa Teresa, Ciénaga de Oro, Córdoba

3145756900

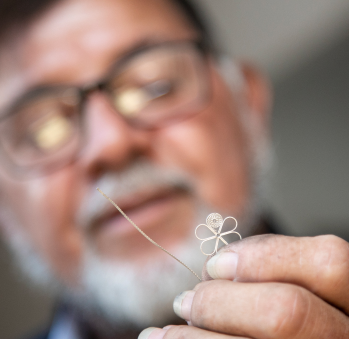

Diego is an heir to the legacy of Mr. Juan Hermenegildo Urán Arias and Mrs. Ida María Arcia Flórez, his parents. They both collaborated with the Chica Arroyo brothers, esteemed jewelers of Ciénaga, alongside whom they gained prominence and entered, through hands-on experience, the realm of filigree. Diego himself was introduced to the world of jewelry-making at the age of eight, assisting his father. Now in his seventies, he bears witness to this craft, deeply rooted into his skin.

Diego takes immense pride in having acquired this skill using a hand-forged tool engraved with the year 1897. This substantial anvil, passed down from his maternal family’s blacksmith shop, witnessed his toil throughout his entire career. Within it, he witnessed metals liquefy and transform into delicate artisanal jewelry pieces. He learned to manipulate gold without relying on acids, instead using salt and lemon—an odd practice born out of financial constraints that, however, came out as good as magical realism. He vividly recalls his mother’s polishing, employing hammock strings or coal, to refine the pieces crafted by his father. He also reminisces about their primary sources of gold: 22-carat dental shims and 24-carat coins. Reflecting on these memories, he describes the meticulous process of filing the gold, melting it into a glass vessel, adding nitric acid, boiling it, and subsequently scraping the fine gold dust, finer than talcum, from the vessel’s surface. He also recollects his father’s ingenuity in creating alchemical bombs combining cyanide with zinc from battery coatings. Mr. Juan Hermenegildo would blowtorch using his mouth: that’s how he welded his pieces. “We were too impoverished,”” he reflects on his parents’ resourcefulness, tinged with a blend of melancholy and happiness. “”We never knew a laminator; everything was done with a hammer,”” he concludes, swollen with joy.

In 1987, his father was awarded the Medal of Artisanal Mastery, yet it was Diego who received the honor. Unfortunately, his father passed away a year later. Fueled by a determination to uphold his family’s legacy, Diego was selected to work at the School of Fine Arts in Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico. There, he shared his expertise for a month and gained insight into additional jewelry techniques. This experience undoubtedly impacted him. He also became proficient in repoussé art, a technique in which he would later excel. He crafted bocachicos—fish from the Sinú river, distinct from Mompox fish due to their eight fins and embossed scales.

Diego believes that what distinguished Ciénaga’s filigree from Mompox’s is its braiding, which resembles the sombrero vueltiao’s weave, so distinctive of his region. Additionally, it incorporates zenú iconography, the trace of his ancestors. He fondly recalls the times when gold-rich currents flowed down from the hills, which the barequeros—artisanal gold miners—would sift through with their trays and sell to the jewelers. He yearns his craft, in risk of disappearing because there are virtually no jewelers left in town.

Just as his parents did, he seeks solace in prayer and has even crafted a meter-long rosary for Pope Francis. It weighed 286 grams. Presently, he customizes jewelry pieces and repairs filigree works for others. He has also ventured into crafting fishing tools, such as steel hooks. Although he could retire, he prefers to remain active, wearing a constant smile as he conceives new jewelry creations. He expresses gratitude to God for his continued well-being and for preserving his family’s pride.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página