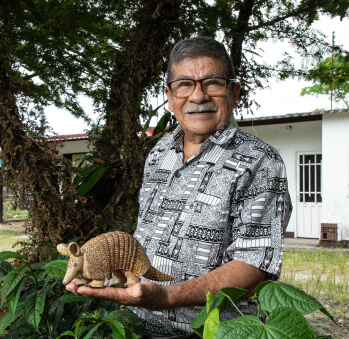

José Israel Castañeda

Workshop: Curticueros

Craft: Leatherwork and shoemaking

Trail: Casanare Route

Location: Yopal, Casanare

SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT

Calle 27 #21-45, Barrio Provivienda, Yopal

3112575155

israel080359@gmail.com

@curticueros_casanare

@curticueroscasanare1

José Israel begins by saying that his story is so long it would take eight days to tell it all, and that really, someone should write a book about him. Still, he gives us a taste of it—a prologue to his adventures. He is the youngest of eight children and was born in Villapinzón, Cundinamarca, but has lived in Yopal for more than twenty years. He carries a bit of Cundinamarca, Boyacá, Risaralda, and the Llanos in him. He says he’s not as tough as a true llanero, but he does know how to ride a horse, thanks to his childhood companion Chipolo, a head-shy horse that would stop short and send its rider flying at the slightest scare—like the flutter of a piece of paper caught on a fence. He has a touch of Boyacá from growing up near the border with that department, where his parents cultivated corn, potatoes, and arracacha. And he claims Risaralda too, because that’s where he set up his first leather workshop and lived well—until the 1999 earthquake forced him to leave.

This artisan, brimming with stories and who once even served as a police officer, admits he wouldn’t be where he is today without his sister, Lidia Castañeda. He misses her every day—“a blessed soul,” as he calls her—since losing her to cancer. If there is one thread that runs through his story, it is his love for his older sister. When he was just a teenager with no clear direction in life, Lidia married a man who owned a tannery on the outskirts of Villapinzón and brought her younger brother to work with them. Without realizing it, she was introducing him to the world he would one day belong to: the world of leather. Those early tanneries, pioneers in leather processing, would later be shut down for polluting the river, and the family moved to Bogotá to open new ones in the city’s south. José Israel went with them, joined the police force, and spent five years serving in Medellín before finally settling in Pereira.

Life would prove to him that leather was his true calling when he was forced to endure one of his greatest trials. After the 1999 earthquake in the Coffee Region, the shop where he made cowboy boots was irreparably damaged: the walls were cracked, the gate wouldn’t close, and demolition was inevitable. So he told his family, “Well, let’s go to Yopal.” They packed up, sold the house, and crammed everything into a Renault 4, bound for the Llanos, where his wife’s relatives lived. At the time, people said vegetables were a money-making business, so José Israel invested his savings into it. Six months later, he was bankrupt. Then he heard the real business wasn’t running a produce shop but delivering vegetables to Orocué, so he tried again. The roads back then were nothing like they are today—it was grueling work. Once, their car even stalled in the middle of a river and they nearly drowned, as if reenacting a scene from La Vorágine, swallowed up by the wild.

His arrival in the Llanos was rocky. Nothing seemed to work out; every attempt led to loss. Until he remembered his old friend: leather. He began asking for hides left over whenever a ranch slaughtered a cow for a workers’ barbecue. He cured them with kilos of salt and sent them to his sister in Bogotá. Slowly, little by little, he found his footing again. And since he was now in the Llanos—land of cotizas—he dove into their history to learn how to make them. He discovered that in earlier times, cowboys living deep in the plains would dry rawhide in the sun, pegged to the ground with stakes. Once hardened, they would trace their feet directly on the leather to cut out soles. A few holes would be punched through, leather strips pulled across, and tied to their feet like sandals. Over time, those crude sandals evolved into the soft leather cotizas with fique or rubber soles that José Israel now crafts.

Whenever this artisan visits Bogotá, he is dazzled by the leather shops in Restrepo. A thousand ideas flood his mind, and he wishes he could take all those hides home to turn into belts, keychains, wallets, and of course, cotizas llaneras. He is a man who has fallen a thousand times and risen just as many, and today he lives happily—not rich, but content, knowing he is exactly where he belongs. His life is proof of it: a lifetime devoted to leather, a path that began with the loving push of his sister.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página