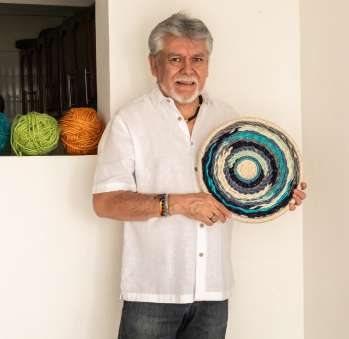

Nohema Cadena de Bueno y María Belse Bueno

Workshop: Arte Pauche

Craft: Woodwork

Trail: Santander Route

Location: Zapatoca, Santander

The pauche tree, with its large green leaves and flowers resembling chamomile, that transition from yellow to green to purple and brown, hides a secret beneath its bark: a soft, foam-like center. It thrives in cooler climates, carrying the scent of untouched mountains. When in bloom, it attracts birds and bees, and the women who know its value plant it during the waxing moon and prune its branches during the waning moon, stripping off the bark and allowing its abundant moisture to dry. They use it to carve the famous figurines of their hometown, Zapatoca, and the birds from the neighboring Serranía de los Cobardes, including toches, blue jays, canaries, and cardinals.

It’s no coincidence that the Bueno women, carvers of the heart of the tree, come from a lineage of women deeply connected to the rhythms and wisdom of nature—knowledgeable of the secrets that have made them midwives, healers, and wise in the benefits of herbs. This tradition began with María Elena Solano, whose father produced cork from pauche for sealing the Santanderean wine bottles. As an adult, she taught her daughter Nohema the arts of carving, midwifery, and delicious cooking. She would take Nohema with her at the age of nine to assist during childbirth, having her boil water for bathing the newborn. By the time Nohema turned fourteen, she was taught how to assist in a delivery, an experience she describes as the most beautiful moment of her life—helping to bring a new being into the world, not knowing how they will live their life, with the only certainty being that they arrived safely.

When her turn came, Nohema started her family with Crisanto Bueno Parra, a coffee and cacao farmer, teaching their children—spread across Bucaramanga and Zapatoca—the craft of working with pauche. She also instructed one of her daughters in the art of healing. María Belse, the eldest, recalls her childhood desire to bite into the soft pauche fruits and breads, sinking her teeth or nails into them. She also remembers the effort it took to evolve from sanding her mother’s creations—arepas, eggs, cheeses and sweet breads—to carving her own. She started small, with apples and pears, but later faced the challenge of carving her mother’s signature birds. Initially, she would break their beaks or tails, but with practice, she became as skilled as Nohema.

As María Belse grew up, she witnessed her mother going out alone to sell her carvings, forming partnerships and traveling with a group of artisan women to Cartagena, Barranquilla, Bogotá, and Calarcá. She recommended the sale of her pieces to acquaintances in other towns and traveled from fair to fair. She learned to gather wild materials and experienced the period when environmental institutions attempted to ban their use, failing to understand that pruning actually benefits the tree, and that the way farmers used it was never destructive. While María Belse worked in various roles, such as a kitchen assistant, substitute teacher, and caregiver, the pauche was always a part of her life. Now, fully dedicated to her craft, she honors her mother with over sixty years of experience, working alongside her and continuing to absorb her many secrets.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página