Jorge Enrique Ayala

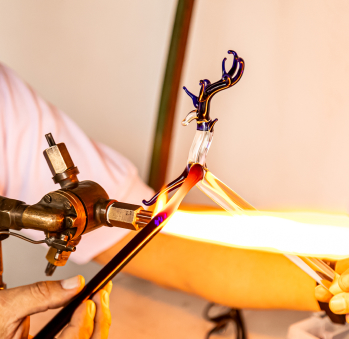

Workshop: Arte y fuego

Craft: Glass work

Trail: Cundinamarca Route

Location: Chía, Cundinamarca

SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT

Calle10 # 17-17, centro de Chía, Cundinamarca

3103214607

arteyfuego56@gmail.com

@arteyfuego56

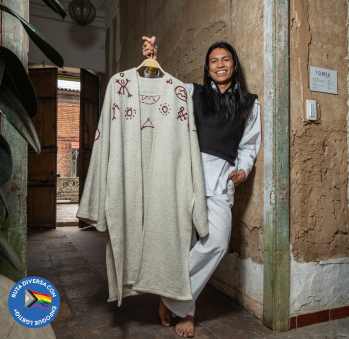

Jorge had plenty of reasons to be proud of his household. His mother was a dressmaker and his father a tailor—not just any tailor, but one who tailored suits for former presidents and state ministers. He always remembers his father impeccably dressed in garments he crafted himself: coats, trousers, and jackets tailored to perfection and reflecting the trends of the time. There wasn’t much money at home, but elegance was never in short supply. Neither was discipline. So, when Jorge brought home a report card with poor grades, his father confronted him: if he didn’t want to study, he would have to start working. And that’s exactly what Jorge did. Today, he’s grateful for that moment, as it set the course for his future.

As a teenager, he began training in glassware production for medical laboratories. It was a complex and meticulous craft guided by Swiss masters, one of whom, Rolf Martin, he remembers fondly. They taught him the art of glass blowing and shaping pieces with exact measurements—250-milliliter glass flasks with an 86-millimeter diameter and a neck that could vary from 34 to 28 millimeters. He spent six months in that workshop school, learning rigor and precision. He worked with them for several years, enough time to master the trade but also to realize that his true passion lay elsewhere. This realization came when French masters introduced him to decorative glasswork.

That’s when he discovered the freedom he wanted to explore. At 25, he struck out on his own. By then, he had completed high school and started university, although he didn’t finish. He tried working for others but found the strict schedules, deadlines, and bosses stifling. While he is disciplined and can happily spend 20 hours seated in his workshop, facing the blowtorch, molding his glass pieces, and preparing orders and designs until his body starts to tingle, that dedication is reserved for his own projects, not someone else’s. Of course, maintaining this conviction has been challenging, and he has faltered a couple of times. Yet, like glass that breaks, the fire within him is enough to be reborn. And so it has.

Jorge speaks passionately about his craft, about what it means to master the “queen of crafts,” as his mentors called the art of glasswork. It requires spatial, emotional, and creative control, alongside manual dexterity. He explains how he takes tubes of varying diameters and begins to shape them into something from his imagination—a Don Quixote or a frog, a puppy or a kitten requested by an amazed child. With patience, he explains that the magic they witness is nothing more than the transformation of matter—how the solid, frozen glass should actually be liquid in its natural state, but by heating it to a pliable, malleable material, he creates a figure that, upon cooling, becomes a magnificent glass piece.

This alchemist has successfully combined his utilitarian knowledge to create refractory pieces that withstand heat with the beauty of decorative design. And he will continue to do so, until the tingling sensation lifts him from his workbench.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página