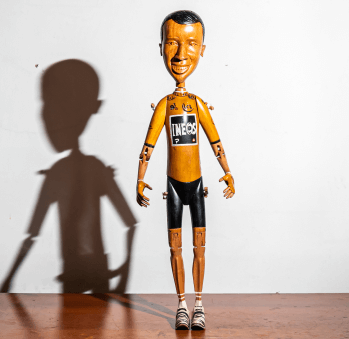

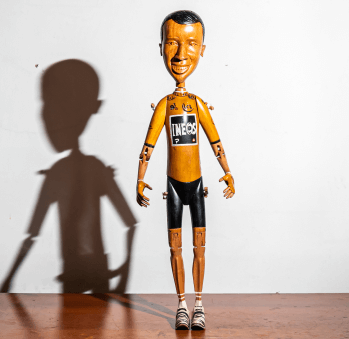

Nicolás Molano

He’s known as Colombia’s own Gepetto, and he wears the name with pride—because he truly deserves it. However, becoming a master doll-maker “Pinocchio style” wasn’t something that happened overnight; it’s been a lifelong journey. Nicolás is lively and easygoing, laughs heartily, and he believes that humor is what keeps him feeling youthful, even though he’s in his sixties. When he looks back, he sees himself in La Concordia, in downtown Bogotá, with few opportunities or resources.

He lost his father when he was just a few months old and, after enduring many hardships with his grandparents in Cali—ranging from recycling, selling ice cream, brooms, lottery tickets, and even car watching—he ended up in the capital to help a relative with a candy and cigarette stand. But he wanted more. During the time when Venezuelan furniture in Louis XV style was highly sought after, he started making his first forays into carpentry to escape poverty. He learned by doing, watching skilled craftsmen, observing, and trying things out. He recalls studying the backrest of a Spanish colonial chair, tracing and trying to replicate what he saw on the wood next to him.

He spent years honing his skills, becoming a master without even realizing it. He also explored other paths: in 1982, he became a rural detective with the DAS, battling miscreants for a while. He felt like his idol, Tony Baretta, the TV cop with a white cockatoo on his shoulder solving crimes. But reality robbed him of this fiction and subjected him to a harsh dose of discrimination, violence, and corruption, leading him back to the city.

There, the call of woodworking returned. As a neighbor of Las Aguas, where Artesanías de Colombia is located in La Candelaria, Nicolás found himself seeking new challenges in his craft. In 1995, the Santo Domingo School of Arts and Crafts was established nearby and later moved to its permanent home close to the Palacio de Nariño. Nicolás dreamed of studying there, hoping to find deeper meaning in his craft. He applied and crossed his fingers. When he got accepted, he says laughing “I’ve never been as happy as I was when I got that call from Santo Domingo School, not even when I got my first mortgage approval”.

He was in the second graduating class and feels immense gratitude towards the school. However, he also realized he already knew a lot, to the extent that after learning what he needed, he became a teacher himself. He had the “wood” for it. He fondly recalls an illustrious visit in 2005 when Don Julio Mario Santo Domingo, the founder of the school, came to his workshop. With childlike excitement, he greeted Nicolás by name and commented that the only thing he didn’t like about Nicolás’s Quijote was the brass shield on Sancho Panza, suggesting a change. This fact set him apart from his peers.

Despite this, Nicolás remained unchanged. He continued to speak with charm and carve his dolls by hand. His repertoire expanded to include characters from Rafael Pombo’s tales, like Rinrín the frog, Simón El Bobito, the poor old lady, and Michín the cat. He made them in all sizes, including nearly a meter tall, showcasing his incredible skill in capturing the character’s features. Over the years, he even crafted a figure of the British cyclist Mark Cavendish, which was so lifelike it captured his expression perfectly.

Nicolás speaks from experience because, like all wood enthusiasts, he feels and draws out the soul of the wood, like he heard a colleague say. He understands the behavior of trees—they grow in spirals, much like the earth, and they store water in specific ways, requiring careful timing to avoid rotting if cut. He shares these rich lessons with grace and joy, fully aware that, despite his deep knowledge, there’s always something new to learn.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página