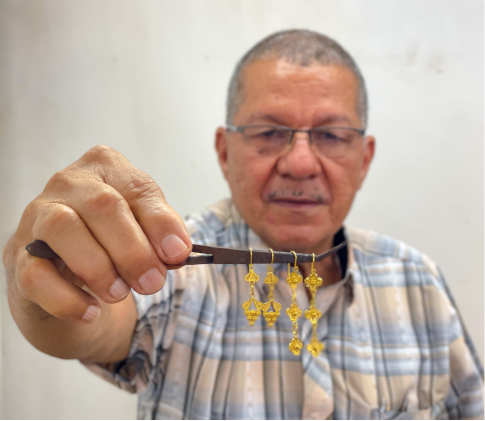

Julián Hernández

Workshop: Dezcu Estudio

Craft: Jewelry and weaving

Trail: Antioquia Route

Location: Medellín, Antioquia

SCHEDULE YOUR VISIT

Calle 43 #88-34 Edificio Torres San Angel

3214291639

julianhdez93@gmail.com

@dezcustudio

@dezcustudio

From a very young age, Julián was spellbound by the sight of the women in his family adorned in jewelry. He loved rummaging through his mother’s, his aunt’s, and his grandmother’s pieces, examining them up close. The adults, of course, resisted—he was just a child, and he might break or lose something. He earned more than one scolding that way. But the fascination stayed with him, along with a lingering question: why was jewelry considered a women’s realm and not a men’s? The enchantment only grew when, in the early 2000s, Aunt Nancy set up a costume-jewelry workshop in her home. Julián would throw himself onto the big table covered in beads, pearls, stones, shiny things, threads, and assembly tools, losing himself in the “do-it-yourself” catalogs scattered around.

Meanwhile, his mid-year and end-of-year vacations were spent on the Córdoba coast, visiting family, the cattle ranch, and the beloved sea. There he would become mesmerized by another of his favorite scenes: watching Aunt Araceli—passionate about pearls—wear her collection. Around that time he developed a habit that stayed with him and eventually became central to his jewelry practice: gathering materials. It began with whatever he found on beach walks—bottle caps, gum wrappers, feathers. Some of those rescued objects survived for years in the family home and later became something more.

He studied Industrial Design and trained as a jeweler through Sena, at Helena Aguilar’s workshop, and at the Envigado Jewelry School. Little by little, thanks to the discipline of contemporary jewelry, he realized it was a medium for expressing one’s own identity and language. In that sense, it doesn’t matter who wears a piece—what matters is what it expresses. When jewelry sheds its gender, it becomes imbued with meaning, aesthetics, and concept; people wear it because they connect with something deeper. Through research—and through that original question about why women wear more jewelry than men—he discovered it had not always been this way. Pearls, for instance, his beloved pearls, were once worn by rulers in India in magnificent ornaments. But then the Queen of England discovered them, began wearing them, and from then on pearls became culturally associated with femininity.

Julián Hernández’s practice revolves entirely around materials. He studies them, pushes them, treasures them. He follows his instinct. If he finds a material that captivates him but doesn’t yet know its purpose, he keeps it for as long as it takes, until the dots connect and the spark lights up. Perhaps this is because another fundamental material in his work is time—time tells him when the moment is right. That’s why he stored away the pearls that, years later, he began carving and slicing after seeing how artisans in France did it, driven by his desire to uncover every possible variation of a single element. Likewise, technique is dictated by his creative needs. Sometimes you have to assemble without soldering, cut, send pieces out to be glass-blown, twist cumare fiber around your leg, clean oysters, or experiment with micro-basketry. And to work with silk or cumare, for example, he learned to weave in a friend’s sewing circle.

Over the years, the childhood beach was replaced by craft fairs—the new place where he discovers materials to feed his treasure collection, his personal library of possibilities. Thanks to this devotion and intuitive attunement, he creates pieces that become amulets for those who wear them, as well as for himself, because they have shown him how expansive jewelry can become when it isn’t bound by gender, but instead embodies identity.

Craft

Artisans along the way

Artisans along the way

No puede copiar contenido de esta página